The work of remembering: the lesson of genocide we never learned

80 years post-Holocaust

It was the 1st of May. We were travelling for three days. They took us in a group to shoot us. We lie down. We lay calmly; it was cold; there was frost at night. When we woke up in the morning, we saw no one. They all ran away. We started running, and the Americans liberated us.

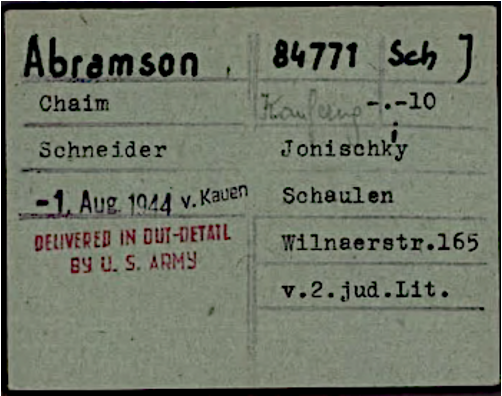

These are the spoken words Chaim, my father, shared in his oral history interview for the Spielberg Foundation. The place he “laid down” is less than two kilometres outside of Waakirchen, a small town in Bavaria, Germany. The “frost” he refers to is 10 centimetres of snowfall. The “travelling” is the Dachau Death March. The exact date when he “woke up” was May 2, 1945, the day he was liberated by the Americans. “The Americans,” more specifically, was the 522nd battalion, which comprised a segregated, all-Japanese American unit.

With the 80th anniversary of Chaim’s liberation from the Dachau Death March – May 2, 2025 – upon us, I realised how very little I knew about the circumstances behind and experiences of the Dachau Death March prisoners. Unfortunately, there is a paucity of historical writings on this particular March. My father’s interview offered no further information than what is written above. For this piece, I located two first-hand accounts of Lithuanian Jews who survived the March - Solly Ganor1 and Zwi Katz2 - as well as the research of Holocaust survivor and scholar Eliezer Schwartz3 that draws on Nuremberg war crime court testimonies of Dachau SS soldiers.4

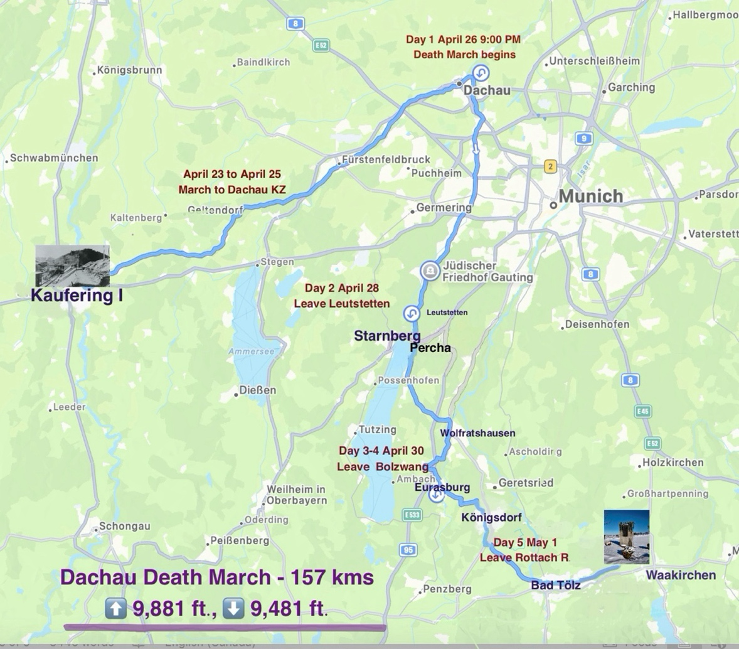

Beginning in the early 1990s, 22 castings of a memorial statue were erected in various German municipalities along the route where the Dachau prisoners were forced to walk. The testimonies of the SS soldiers provided specific locations, enabling me to map with some accuracy the Dachau Death March. I spent weeks imaginarily walking (on Google Maps using satellite images) the same roads my father marched 80 years ago. It did not escape me how the beauty of the rolling Bavarian countryside was transformed into yet another concentration camp. I became overwhelmed by an array of emotions, but none was greater than rage - how is that we are living amidst a present-day genocide?

Memorialising the Holocaust is meant to remember the lives and communities lost, to fight against anti-Semitism and to serve as a reminder that all lives are sacred and need protecting. And yet, anti-Semitism 80 years later is on the rise, and if we look around us, genocides have not been deterred. While I share my father’s liberation story and a largely untold piece of history of the Dachau Death March, I shift my focus to the genocide the Israeli State is inflicting on the Palestinian people. They are inextricably linked.

Chaim was a Holocaust survivor of the Shavl (Šiauliai) ghetto, the Dachau Concentration Camp, and the Dachau Death March. At the age of 17, he left his home and moved to Shavl, the second largest city in Lithuania at that time. There, he opened a small tailor shop, married Lea, and had two children: Samuel and Sara. In August 1941, shortly after the Germans occupied Lithuania, the family was forced to move into one of the two Shavl ghettos. Ghetto life was brutal. The work was backbreaking, there was little food, beatings, and public hangings that all the Jews were forced to witness. And in November 1943, a kinder-aktion (children’s roundup) occurred, and Sara was transported to Auschwitz, where she was among the 725 children who were gassed.

Beginning July 15, 1944, with the Soviet army approaching Lithuania, the ghetto was liquidated and set ablaze. The Jewish prisoners were packed in cattle cars and transported to Stutthof Concentration camp, where the healthy men were separated from the women and children. That was the last time Chaim saw his family. Samuel was immediately transferred to Auschwitz and presumably gassed. Lea survived the war but died days after the war ended. The next morning, Chaim was transferred from Stutthof to Dachau to confront, as he said, “an even greater hell.”

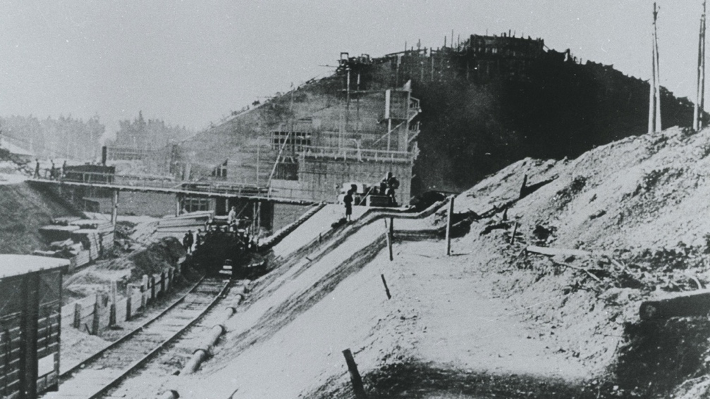

On August 1, 1944, he was moved to one of Dachau’s sub-camps, Kaufering, a complex of eleven camps, each with thousands of slave labourers. I am not sure to which of the Kaufering Camps he was sent, but most likely it was Kaufering I. There, the prisoners were forced to build underground bunkers to house the future Messerschmitt Me 262 jet fighters. The Nazis signed contracts with construction companies; in this instance, the Leonhard Moll company from the Organisation Todt (OT) was awarded the contract, reaping enormous profits from using slave labourers.

The slave labourers in Kaufering worked 12-hour days hauling cement, building railway embankments and when necessary, cutting down trees. The bunker comprised a half–cylinder of concrete: 1,300 feet long; at the base, it spanned more than 275 feet; was 95 feet high; and nearly ten feet thick.

Solly Ganor, another Lithuanian Jew and survivor of Kaufering X, described what he saw at the Messerschmitt bunker when his work assignment was to accompany a SS guard to deliver some machine parts. This place, close-up, Solly said, “was even more frightening” than the rumours he had heard:5

Along the sides, scores of prisoners stood on platforms handling huge flexible hoses that spewed wet cement into the spiked gridwork, while others moved about with shovels and buckets. Everywhere we looked we saw what looked like thousands of men in striped uniforms moving about the compound, carrying lumber, iron rods and sacks of cement. It was like an enormous, evil hive.

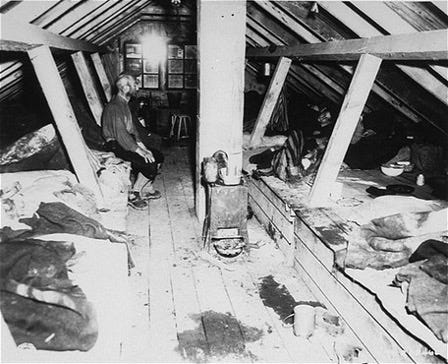

At the end of the workday, the Jewish prisoners returned to equally abhorrent living conditions. Chaim described their dwellings as partially underground structures with tin coverings, and sleeping on platforms where they were tightly crammed. Every 24

hours, they received a small piece of bread with water. Given only 250 calories of food a day, the life expectancy of a prisoner averaged four months. There was no showering the whole time they were there, and lice and other diseases, such as typhus and tuberculosis, were omnipresent. “But somehow we lived,” Chaim said.

THE DACHAU DEATH MARCH

Fearing the advance of the Allies, the evacuation of Dachau and its sub-camps began the last week of April 1945, and the prisoners were forced to march to the main camp and then south toward the Austrian border. There has been some debate as to the rationale behind the southern direction of the Dachau Death March. Yehuda Bauer, a historian and Holocaust scholar, ruminates that perhaps the prisoners were either used to build bunkers along the German/Austrian border; or, fearing their imminent defeat, the Nazis, could use the prisoners as a last effort bargaining chip; or probably, the Death March was yet another strategy of the Nazi’s mass murder agenda.6

Few words can accurately describe the sufferings the prisoners withstood over the following days. “The most important thing on this march,” for Zwi, “was to endure the hardships. A few more hours, sometimes only a few minutes, another kilometre, even a few hundred metres.” 7

Dressed in threadbare striped uniforms, some had wooden shoes, others barefoot, they were paraded through 18 Bavarian towns in Southern Germany. There was no food, and they walked 10-15 hours a day.

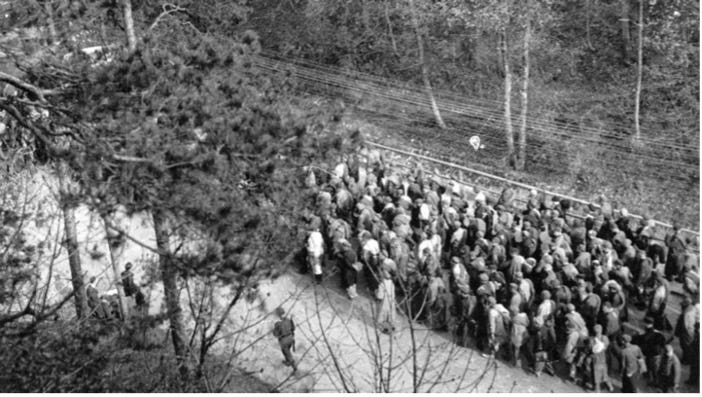

On April 24, 1945, 3,700 Kaufering prisoners set out on foot over two days to the main Dachau camp. After spending a day at Dachau, on April 26 at 9:00 PM, 6,887 prisoners (1,213 Germans, 4,150 Russians and 1,524 Jews, of which 341 were women) started marching towards the Austrian border. The Russians were at the head of the group, the Jews (Chaim was one of them) were second, and German prisoners were at the back. The Nazi guards, according to Solly, “were increasingly nervous, beating and cursing the stragglers. Many of the guards had dogs on leashes, big German shepherds and especially vicious Dobermans that barked and snapped constantly at prisoners who strayed too close.8

As the prisoners set out from Dachau, the weather took a dramatic turn for the worse. In the heavy rain and cold, they marched all night through the suburbs of Munich until 9:00 AM when they reached Leustetten, five kilometres north of Starnberg. According to Solly, they “camped in a wooded area huddled together trying to retain a little body heat.”9

The following morning - April 28 - they set out early. Their plan was diverted because the German soldiers were deeply worried about the proximity of the Allied troops and rerouted the prisoners south along the eastern shore of Lake Starnberg. When they reached the village of Berg, they headed southeast towards Wolfratshausen, then southward. The names of towns and villages were mostly not remembered by the prisoners, but both Zwi and Solly remembered Wolfratshausen, which Zwi described as: “a strange name, … a place unknown to me, somewhere far away, where the wolves held council.”10

Following a very long day, the prisoners were brought to a wooded area four kilometres south of Wolfratshausen and spent the next day in the forest. Solly remembered hearing “faint explosions,” which they hoped were from American field artillery. That night, they were marched out in groups of 100, each guarded by six armed guards and dogs. Prisoners were collapsing from exhaustion, hunger and cold. If a prisoner fell, he was either shot by soldiers or attacked by the dogs. All Solly could envision were bodies of some of the last Lithuanian Jews in Europe littered throughout the picturesque Bavarian countryside. The date was April 30, and the snow came down hard.

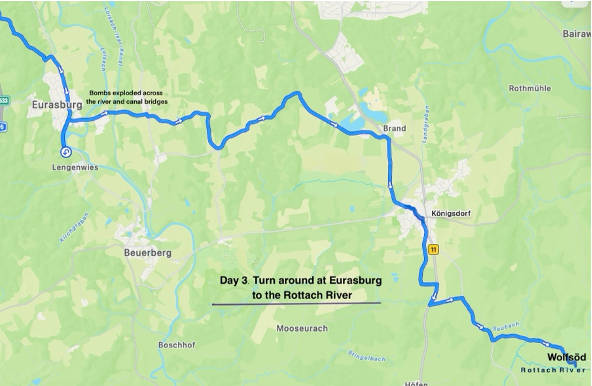

The prisoners continued southward. As they passed the town of Eurasburg, orders were received to reroute as the US army was looming. The Nazis reversed their steps back to Eurasburg and then headed east on a road that crossed the two bridges over the Loisach River and Canal. In anticipation of and to impede the American advance, the Germans planted bombs on these bridges.

With great urgency, the Nazi soldiers rushed the prisoners across the bridge. Only the Jewish and German prisoners successfully crossed before the bombs were detonated. They continued marching southeastward and spent the night in the remote area of the Rottach River valley. If it were not for the intervention of a German officer who, with a gun, confronted the March commander, the Dachau prisoners would have been exterminated.11 The weather continued to be cold, and heavy rain fell throughout the night. In the morning, the prisoners, exhausted, fatigued and starving, were led up from the river valley. There was a weariness, and a shadow of doom weighed heavily on the prisoners: “We were like a column of gray ghosts shuffling along heads down… Death holds no horrors now.”12

As they marched through the centre of Bad Tölz, there were no longer orderly lines of the prisoners, and chaos ensued. Many prisoners began begging for food. The guards, losing control, randomly began shooting at the prisoners. They no longer worried that locals were witnessing this onslaught. Solly wrote, “We must have lost a thousand people that morning alone…. At the rate it was going they would soon run out of ammunition.”13

The prisoners, accompanied by heavy and continuous snow, continued marching eastward through the villages of Greiling and Reicherbeuern. Zwi was overwhelmed by the despair that embraced him: “I am consumed by bitter sorrow and grief. Even worse are the thoughts that torment me: The luck that has always been on my side until now has left me, and I am now probably going my last way.”14 As I read these words, my thoughts turn to Chaim. How did he have the physical and psychological drive to keep moving? Perhaps it was the dim hope that his wife and son were still alive, or perhaps there were no thoughts, no motivation; he was on autopilot, one step at a time moving forward, going somewhere, going nowhere.

Two kilometres east of Waakirchen, they were led into a wooded area. The prisoners were forced to lie down on the snow-covered ground. Not expecting to survive the night, they fell into a deep sleep. By the early hours of May 2, ten centimetres of snow had fallen. When they awoke, both Solly and Zwi heard a peculiar sound – silence: no soldiers shouting orders, no dogs barking! Sometime during the night, the German soldiers had run away.

Early in the afternoon of May 2, a group of scouts from the 522nd Field Artillery Battalion of the US Army was travelling towards the Austrian border to capture Hitler's vacation home in Berchtesgaden. As they approached Waakirchen, they saw an open field with several hundred “lumps in the snow.” When the soldiers looked closer, they realised the “lumps” were people, “in many cases unable to move. Some were shot, and some were dead from exposure...” Hundreds were barely alive. Some roamed aimlessly around the countryside. Chaim was one of the roamers.

The 522nd battalion comprised a segregated, all Japanese American (second generation - Nisei) unit. There is a deeply sad irony to this story. Many of the Nisei volunteers from the US mainland came from internment camps, set up by the American government for unfounded reasons of national security. The Nisei soldiers were ordered to keep quiet about this role in liberating the Dachau prisoners, and to this day, they have never received recognition for their heroics.

The Genocide that was, the Genocide that is!

The Americans gave my father canned meat; this was not so good. Becoming deathly ill, he ended up in the hospital for a few days. From the hospital, with nowhere to go, Chaim was floundering. He was the only one in his family to have survived. He lost his mother, sisters, brothers, nieces, nephews, and his wife and children. He lost his home; he lost his country; he lost everything. With nowhere to go, Chaim spent the next few years in displaced persons camps in Germany, Italy and Cyprus.

With the end of the war, there were up to 11.5 million displaced persons – Jews, Russians, and Poles – and Europe was in shambles. Desperately wanting peace, 50 countries assembled to draft a charter to prevent a future war like World War II. The Security Council was established to enforce the key principles of the UN. The Council was contentious from the start as the five permanent members – China, France, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States – each had veto power.

Beginning in the 1960s, with anti-Semitism on the rise, Holocaust Museums opened worldwide to educate the public about the Holocaust and the lingering threats of anti-Semitism, racism and hatred. The mission statement at Yad Vashem, the world Holocaust remembrance center in Israel, is to strive “towards a more ethical future for humanity as a whole.” Similar themes of social justice are pervasive in the mission statements of most Holocaust centres. And the slogan Never Again came to be. Implicit in its meaning was Never Again for all people.

Yet with supposed safeguards in place, the world has failed miserably to prevent crimes against humanity, ethnic cleansing, and/or genocide. The UN’s intent to remove politics from conflicts that lead to genocide has done exactly the opposite. Security Council countries would vote to favour their allies even though unspeakable atrocities were committed, examples being in Rwanda (1994), in Kosovo (1998-99), and in Darfur (2004).

On October 7, 2023, Hamas penetrated Israel’s Iron Dome and attacked communities near the Gaza border. The largest slaughter of Jews since World War II took place: 1,139 were murdered, 8,730 were injured, and 250 were kidnapped and taken back to Gaza.

And immediately, Israel declared war on Hamas, unleashing a massive onslaught on the Palestinian people living in Gaza. About 90 percent of Gazans have been forced to leave their bombed homes, and the Israelis have consistently denied aid (food and supplies) and water to the Gazan people; mammoth numbers of children are dying from malnutrition; the infrastructure has been destroyed – roads, hospitals, schools, etc. The war was supposedly against Hamas, but the reality is that all Palestinians have been collectively punished.

Yet many Jews and Western nations refuse to label what is happening in Gaza a genocide, even though all the criteria that define genocide are met. Efforts by the United Nations Security Council to put a permanent end to the war in Gaza have unfailingly been vetoed by the United States, Israel’s closest friend and ally. Furthermore, there has been a steady stream of weapons and bombs shipped to Israel from the US and other liberal democracies, supposedly committed to ensuring genocide never happens again.

There is a moral apathy occurring in Israel where Israelis do not see themselves as a perpetrator group. Ori Goldberg, an Israeli political commentator, believes, “Palestinian pain does not register on the Israeli radar…and a lot of us view Palestinian pain as Palestinians’ fault… Israel does not acknowledge its actions in Gaza [and] does not see them as anything but, by necessity, required by self-defence.” What we are witnessing is a population whose values support the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians in Gaza, underpinned by a heinous belief that the Holocaust provides all the justification needed.

The Jewish communities worldwide have just commemorated Yom HaShoah (Holocaust Remembrance Day). There are profound concerns among Jews about the recent rise in anti-Semitism. Many of the commemoration speakers were Holocaust survivors who shared their individual stories to forewarn the world what happens when a state loses its moral centre. Politicians attended in impressive numbers, vocalising their concerns about the evils of hate based on race, religion or ethnicity. The double standard that defies all logic is staring us in the face.

Holocaust commemorations are meant to make this world a more humane place. Instead, whether out of hate or fear, monstrous and brutal acts of injustice that Israel is inflicting on the Palestinian people are condoned and justified. “Never again” has become a trope, only relevant to the Jews.

Eighty years after World War II, we find ourselves perhaps in a worse place than before the war. Institutions such as the UN Security Council and the International Court of Justice are powerless in ending the Gaza genocide, and like Israel, many Western countries possess a moral apathy immune to the Palestinians.

In his acceptance speech for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1986, Elie Wiesel’s words offer a precautionary warning: “silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.” There has been an attempt to silence Jews speaking out against Israel, labelling us as Anti-Semitic, and, in my case, I have also been accused of betraying my parents’ memory by comparing the Holocaust to the genocide in Gaza. The real betrayal of my parents’ memories and all the lives that were needlessly and horrifically lost during the Holocaust is to stand silent as the world did in World War II, to turn a blind eye to the mass atrocities in Gaza, and to justify them in an unjustifiable way.

Solly Ganor, Light One Candle: A Survivor's Tale from Lithuania to Jerusalem, Kodansha America, Inc.: 1995.

Zwi Katz, “Todesmarsch von Kaufering ins Ungewisse”. Dachauer Hefte, Volume: 18: 200-211, 2002.

Eliezer Schwartz, The Death Marches from the Dachau Camps to the Alps during the Final Days of World War II in Europe. Dapim: Studies on the Holocaust, 25(1), 129–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/23256249.2011.10744408. 2011: p4.

Eliezer Schwartz, The Death Marches from the Dachau Camps to the Alps during the Final Days of World War II in Europe. Dapim: Studies on the Holocaust, 25(1), 129–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/23256249.2011.10744408. 2011: p4.

Ganor, p.297

Yehuda Bauer, “The Death-Marches, January-May, 1945,” in Michael R. Marrus (ed.), The Nazi Holocaust: Historical Articles on the Destruction of European Jews, vol. 9 (London: Meckler Westport, 1989), pp. 491-509.

Katz, p.211

Ganor, p.340

Ibid.

Katz, p.203

Schwarz, p.145

Ganor, p.344

Ganor, p.344

Katz, p.206

Wow Zelda- Not only is it unfathomable to me that Chaim or anyone could survive that march- but that you can image,write and confront this reality and not completely throw up your hands, scream, and loose all hope. I learn so much from your writing and sincerely appreciate your work.Thank you.

This is excellent Zelda, thoughtful, shocking and a real tonic in a way. How your dad and others survived...